Today, I joined a Python-focused Discord server for code review. My algorithm used a nested loop to iterate within the range of years and my new list of lists. This didn’t feel very elegant, so I wanted some feedback.

column_names = ["P_ID"]

# Iterate through year intervals

for current_year in range(earliest_year, latest_year + 1, 2):

column_names.append(

str(current_year) + "–" + str(current_year + 1)

if current_year != latest_year

else str(latest_year)

)

for row in rows:

...

We discussed ways that it could be refactored. One member brought up using a Cartesian product using itertools.product().

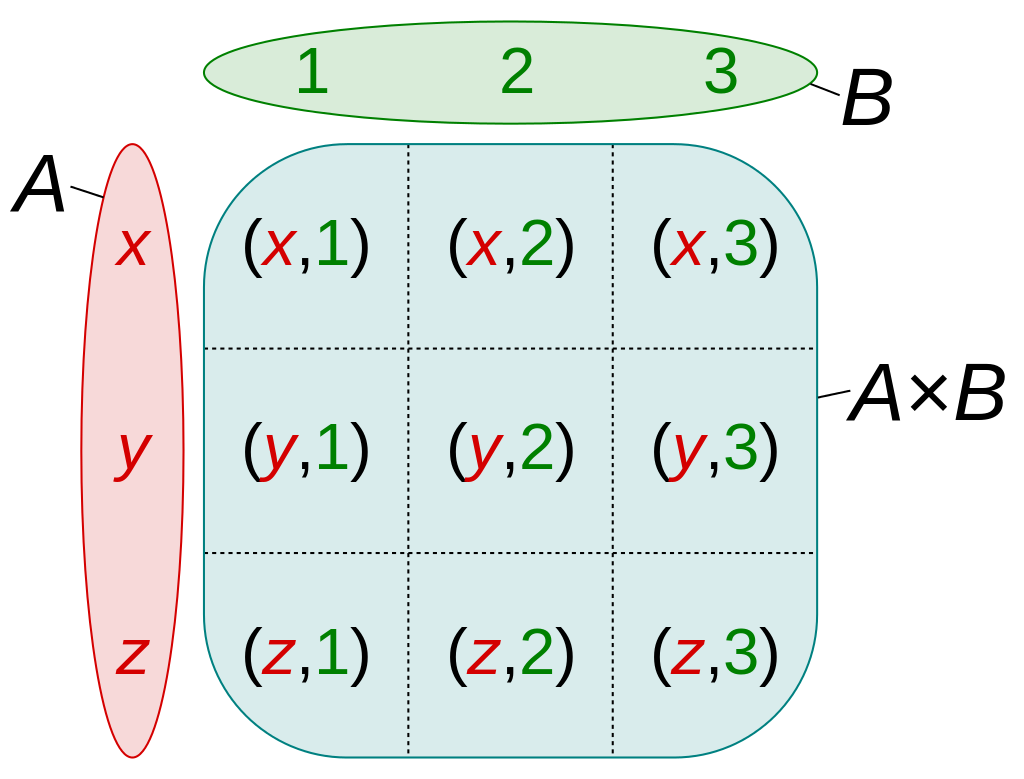

This sounded smart, but what is a Cartesian product? It turned out to just be the set of all pairs whose first element is from the first set and second element is from the second set. For example, here is the Cartesian product of {x,y,z}×{1,2,3}.

If I replaced my nested loop using itertools.product(), it would look like this:

product = itertools.product(range(earliest_year, latest_year + 1, 2), rows)

for year, row in product:

...

But, there wasn’t a good method to get the column names this way.

I then thought that I might as well create a DataFrame before the loop and append rows to it,

but I read through the documentation of DataFrame.append()

and saw that this was not recommended.

The Notes section reads,

Iteratively appending rows to a DataFrame can be more computationally intensive than a single concatenate. A better solution is to append those rows to a list and then concatenate the list with the original DataFrame all at once.

The better solution was essentially what I had before, so I decided to leave it for now.

One other suggestion that I received was to use formatted string literals. Reading this article, I learned that formatted string literals, or f-strings for short, are an easier way to include the value of expressions inside strings. This interested me, and I added them to my code. Here are some before and afters:

str(current_year) + "–" + str(current_year + 1) # Before 1.

f"{current_year}–{current_year + 1}" # After 1.

"Done! Processed data saved to " + file_output # Before 2.

f"Done! Processed data saved to {file_output}" # After 2.

These weren’t big changes, but using f-strings felt much better than adding strings together.

Finally, I read about type annotations from this article, and I added them to my code. These just helped me remember how things worked a little easier.